Successful movies strike a balance between letting the audience know what’s going on through things like exposition or internal monologue and trusting the audience to figure things out. And, as an audience, we also want both. We want to be told where the story and characters stand, and what the rest of the film might hold. But we also want to feel like we’re participating in the movie. It is the magic of a genre like ‘whodunit’ murder mysteries: We are trying to solve the case alongside, and hopefully ahead, of the investigator.

It is easy to throw the balance off. The right amount of exposition or internal monologuing contrasted with character building gives us a glimpse into the future, but because we’ve figured it out for ourselves, we’re excited to find out if we’re right. People love being right. Too much exposition or internal monologuing doesn’t just give away what we’re yet to see, but it makes us feel stupid, talked-down to, or both.

We do have to give writers a bit of slack here because striking that balance can be hard, especially with a modern audience that is constantly checking baseball scores or Twitter during the movie. Large blockbusters also have to appeal to countries outside of North America, so using certain slang or phrases common here would miss the mark in audiences from Czechia to China.

Watching Die Hard With A Vengeance a few days ago, one scene really stuck out to me as something that builds anticipation and trusts the audience to figure it out. It isn’t even complicated, but when the payoff hits, it hits in a big way.

For anyone who hasn’t seen the third Die Hard movie in a while, our heroes are John McClane (Bruce Willis) and Zeus (Samuel L. Jackson). The hook of the movie is that the villain is making John and Zeus solve a bunch of riddles in locations all around New York City, and any failure to comply results in bombs detonating. One is a word riddle as follows:

As I was going to St. Ives,

I met a man with seven wives,

Each wife had seven sacks,

Each sack had seven cats,

Each cat had seven kits:

Kits, cats, sacks, and wives,

How many were there going to St. Ives?

It isn’t a math problem, it’s a word problem, and they figure out it’s just one person (the very first line). We are being primed by the writers that this isn’t necessarily a full-blown action movie, but one that requires some mental dexterity. Not long after is the second puzzle, which is a math problem, and something they also solve.

At this point, McClane figures out that the villain isn’t just messing with him, but distracting the cops from the real purpose, and that’s a gold heist from the Federal Reserve in New York. The villain and his group are all European (many/most former East Germans) and of the ones we do meet, it is obvious that English is their second language. At this point, we know the following:

- McClane not only is a shoot-‘em-up cop, but one with mental acuity.

- The writers are encouraging us to solve the problems alongside McClane.

- American English is not the native language of our bad guys.

That’s what makes the scene where McClane goes to investigate the Federal Reserve so smart.

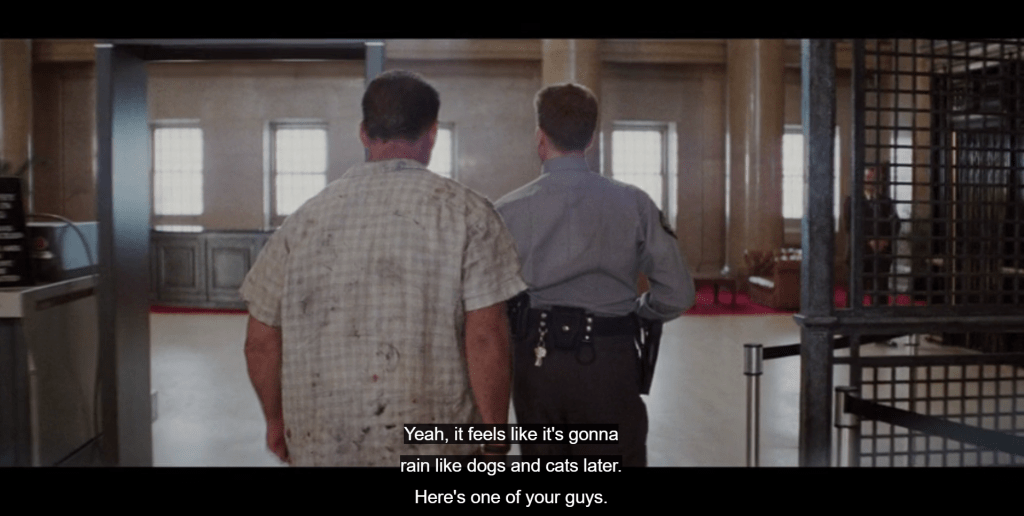

The villains have taken over the Federal Reserve (all the cops in New York are searching for bombs), so the security at the front desk is one of the bad guys pretending to be security. He offers to show McClane the basement to investigate (they are planning to kill him, of course), which McClane accepts. As they’re walking to the elevator and making small talk, the bad guy says this about the weather:

Of course, anyone with American (or Canadian) English as their first language knows the expression is ‘rain like cats and dogs’. The villain reverses the two animals, and that’s the first giveaway.

Once they get into the elevator, and the small talk continues, the same bad guy mentions he avoids taking the stairs on a hot day like they’re enduring, followed up with this:

‘Lift’ is the term used in the United Kingdom to describe the elevator. Almost anyone watching this movie in 1995 in North America would not use the word ‘lift’ to describe an elevator. They would just say elevator. That the bad guy uses the term ‘lift’ is another clue for McClane that this security guard isn’t from the Bronx.

The final clue is the badge number from one of the bad-guy cops as it’s the same badge number from someone McClane met earlier in the movie, and this isn’t him. But because of the first two English slip-ups, we already know what McClane knows, and then the action portion of this scene begins.

This isn’t complicated. It is one idiom expressed in an incorrect manner and one word that is a synonym for elevator but would not be used by an American-born security guard in New York. Those two bits of information allow the audience to solve the puzzle ahead of McClane, make us feel smart, and build anticipation for the ensuing gun fight, all while allowing McClane to use his mental sharpness to figure out what’s going on before pulling out his gun.

This is in direct contrast to Jurassic World Rebirth, which came out this past week. To be clear: I enjoyed myself watching the movie and thought some of the dinosaur scenes were very, very well done. The acting from most of the cast is great, too.

But the ending is infuriating. Without spoiling anything, our lead character is Zora Bennett, played by Scarlett Johansson. She is a mercenary who is hired to retrieve dinosaur DNA. The first act of the movie goes to great lengths to show us that she’s about getting paid, and not about morality. But this is a Hollywood movie, so she goes on an arc to go from a mercenary focused on finances to a person trying to uplift the world around her.

The final scene involves her making a decision that would hurt her financially but help people around her. As an audience, we just spent two hours with her and watched her go on this journey. We know what decision she’s going to make. But the final bit of dialogue in the movie is her saying out loud, and quite clearly, exactly what she’s going to do. It is completely unnecessary. We have seen her eschew her cold, calculating, dollar-driven persona in the first act and evolve to the person she is in the third act. There is no reasonable interpretation of what decision she’s going to make at the end other than she will help people. AND YET, for some reason, she has to say it out loud for everyone. Maybe things in blockbuster movies have to be, for lack of a better word, dumbed down to appeal to as many people as possible, but it’s hard to imagine that if they left that line of dialogue out that there would be any noticeable percentage of the audience assuming that the Zora Bennett character would just fuck everyone over. It is insulting to anyone who just spent their money and took hours out of their day to enjoy the movie.

And it is an enjoyable movie. There are things I don’t like about it other than that bit at the end, but by and large, it’s a fun movie to sit down with for two hours. But that ending feels like something a host would say at the end of a TV program for 3-year-olds. Studios, writers, and filmmakers need to trust their audience, or they risk losing them in the future.